63. Dusty Wunderlich on FinTech Financing: Entrepreneurs Helping Entrepreneurs

Key Takeaways and Actionable Insights

FinTech sounds like the latest over-hyped tech bubble. But it has a much more fundamental importance in entrepreneurial economics. It brings entrepreneurs the best-priced capital in the marketplace. Dusty Wunderlich explains on the Economics For Entrepreneurs podcast #63.

Consider these findings from a 2017 report from the G20 Global Partnership For Financial Inclusion, titled Alternative Data: Transforming SME Finance.

Access to financing remains one of the most significant constraints for the survival, growth, and productivity of micro, small and medium enterprises (SME’s).

Digital SME finance, using alternative data, offers an extraordinary opportunity for addressing…this problem.

The world’s stock of digital data will double every two years through 2020. Every time SME’s and their customers use cloud-based services, conduct banking transactions, make or accept digital payments, browse the internet, use their mobile phones, engage in social media, buy or sell electronically, ship packages, or manage their receivables, payables and record-keeping online, they create digital footprints. This real-time and verified data can be mined to determine both capacity and willingness to pay loans.

A rapidly growing crop of technology-focused SME lenders are putting the use of SME digital data, customer needs and advanced analytics at the center of their business models, setting forth new blueprints for disrupting the SME lending status quo.

The report refers to 800+ innovative digital SME lenders. Colloquially, we can refer to them as FinTech.

Dusty Wunderlich, a subject matter expert and seasoned investor in the FinTech field, discusses this lending landscape.

Entrepreneurs need capital in the present to deliver goods and services to consumers and customers in the future.

Entrepreneurs take scarce resources and apply them to what they believe the consumer will want at a future date. In order to do that entrepreneurs need capital in the present so they can deliver on those goods and services to the consumer in the future in the hope that their forecasting is correct.

That’s why entrepreneurs need to understand capital financing and modern day capital markets.

Access to capital has historically been difficult and expensive. Today, it’s becoming easier and less expensive, aided by the digital data revolution referred to in the report quoted above. It’s important for entrepreneurs to be familiar with the new field of FinTech and how to navigate it.

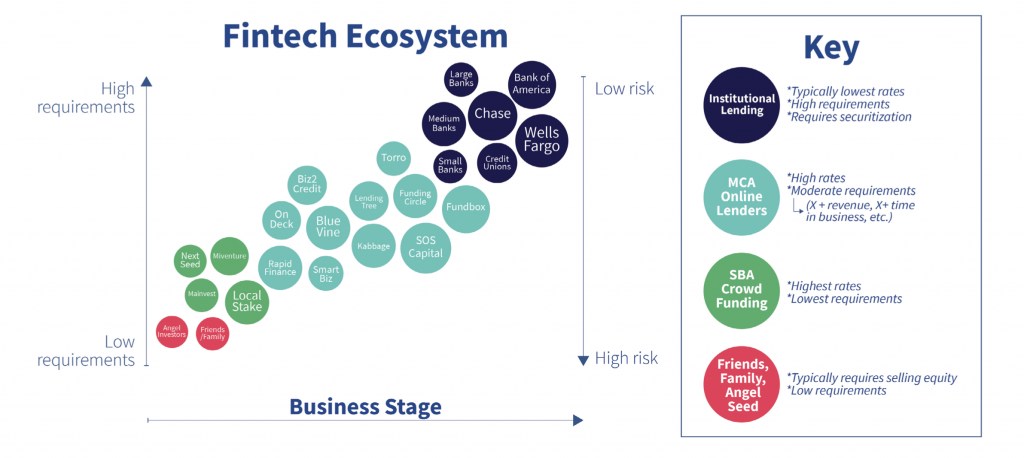

Dusty Wunderlich suggests that entrepreneurs map out the financing alternatives on the axes of their own business stage versus the cost of capital.

Cost of capital refers not just to interest rates and fees, but to the requirements that lenders can impose on entrepreneurial borrowers. At the very earliest stages, “friends and family” lenders, angel investors and seed stage venture funds will all require equity stakes, and ratchet up those stakes via deferred interest and debt-to-equity conversion requirements. These early investors perceive themselves as taking a high amount of risk, and the start-up entrepreneur typically has little or no collateral or leverage in negotiation. The best negotiation stance is to generate competition among investors with the quality of the customer value proposition and the business plan and revenue model.

Fintech financing is now available at the earliest of entrepreneurial growth stages.

Today, from the very outset of the business journey, start-ups and small businesses can access a range of financing types – debt, convertible notes, equity and SAFE’s (Simple Agreement For Future Equity) – via crowdfunding platforms like nextseed and others like it. Marketing your business to investors on platforms like these taps into your existing skills in marketing and social media, and doesn’t require you develop capabilities in pitching your business that you might not have mastered.

As you advance along the growth curve, FinTech options expand and may offer you the best-priced capital on the market.

As a result of the expansion of FinTech based on alternative digital data sources, the potential for connecting your particular business to a well-matched and well-priced source of capital is greater and more precise than ever. Dusty cited a couple of examples like Kabbage (where, incidentally, entrepreneurs can currently get help with PPP loans). There are several more. Because of the competition in the FinTech market and the quality of the information they utilize, capital from these lenders is well-priced – probably approaching Mises’ originary rate of interest, Dusty observes, in a testimony to Austrian free market principles.

It is when your business represents the least risk to lenders that big banks offer their high-requirements business loans.

At a later stage of your business journey, banks will lend money against collateral and will impose additional onerous requirements and loan covenants. The entrepreneurial embrace of uncertainty is not for them! Bank financing is at the top when it comes to cost of capital and is to be approached cautiously. It is with bank financing that entrepreneurs become entangled with the negative effects of Federal Reserve repression of interest rates, that can mislead them into making incorrect investment decisions.

The cost of bank financing for mature companies revolves more around terms and covenants than interest rate percentage points. Banks are transactional, whereas entrepreneurs are operationally minded. This can cause a lot of friction if covenants, terms and triggers are not properly set. Entrepreneurs must pay attention to every detail in the loan contract. Great businesses can be ruined because of draconian covenants and triggers banks put into their loan contracts.

Indicated action: Entrepreneurs will be well-rewarded for fully investigating and understanding the emerging world of FinTech and digital SME finance. Be sure to calculate the full cost of capital – not just interest rates – and weigh all options.

Free Downloads & Extras

“Financial Capital Options for Businesses At All Stages”: Our Free E4E Knowledge Graphic

Understanding The Mind of The Customer: Our Free E-Book

Start Your Own Entrepreneurial Journey

Ready to put Austrian Economics knowledge from the podcast to work for your business? Start your own entrepreneurial journey.