Quantum Economics, Potential, And The 4V’s Business Model.

To get your head around quantum mechanics, it’s necessary to be able to think about a space that’s between reality (called spacetime in the language of the science) and imagination, something that doesn’t exist. This half-way house, this in-between, is not unreal. But it can’t be observed or verified. Some of its inhabitants will become real and verifiable and some won’t, never to be observed at all. A way to think about this in-between is as potential. Potential is sometimes realized, and sometimes it isn’t.

In her book Understanding Our Unseen Reality, Ruth E. Kastner explains how potential can be realized in quantumland. It takes the form of a transactional process, in which a quantum object that she calls an emitter sends out an offer wave. Under certain conditions, another quantum object, which she calls an absorber, can receive the offer wave and send a confirmation wave in return. If the confirmation is a mirror image of the offer, the two objects have formed an incipient transaction. If there is only one offer and only one matching confirmation that is an exact mirror image, the incipient transaction becomes actualized and real. It becomes, in Kastner’s words, “A brick’, an observable, verifiable event in spacetime. (pp 48-53)

I am quite sure I have oversimplified quantum theory. However, it’s in the good cause of making an analogy that is useful for real-world practicing entrepreneurs and businesses.

Austrian economics is quantum economics. Quantum mechanics is the study of behavior and properties and interactions of the smallest units of energy in the universe. One of its revelations is that “the rules are different” at this scale. The rules of classical physics do not apply. Austrian economics is the study of the smallest unit of energy in the economic system, the individual. The term that is used in economic science is methodological individualism: the study of the behaviors and properties and interactions of individual people and how they propagate into processes like value creation, and economic growth, and into structures like firms. (Here’s a white paper that explains in detail.)

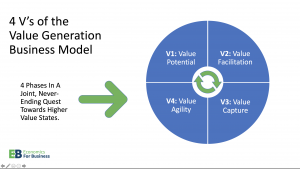

An example of an emergent process is the Austrian Business Model, a framework for profit-making operations for businesses. The essence of the Austrian Business Model, the engine if you will, is the core value generation process we call 4V’s. The 4V’s represent a rolling, recursive, repeating value process for firms to successfully bring new innovation to the market. The 4V’s are Value Potential, Value Facilitation, Value Capture, and Value Agility.

In quadrant V1, Value Potential, is in quantumland. It’s not yet real, but it can be. Think of it as the space where the consumer is sending out offer waves, just like a quantum object. These offer waves are a little hard to process. The consumer expresses dissatisfaction, or unease with the current state of their consumption experience. Things could be better. The wine could be more to their taste, or it could be less expensive. They like the room afforded by their SUV but they’re a bit unsure whether they can put up with the mpg levels. They like going to restaurants but it might be nicer if the restaurant came to them. Maybe they feel they’re not getting all the possible benefits that they could from the internet. Or Netflix. Why is zoom so hard to use? Why does my bank treat me with such disdain? Why can’t I eat as much chocolate as I would like? Why is healthcare so expensive? I’d like to earn a degree, but I’m not sure if it’s worth the 4-year commitment or the money. Why is the CFA exam so hard? Why is dentistry so painful? Is my dog enjoying its food? I hate having acne. I have a headache. Sometimes, I feel a bit lonely.

Consumer sentiments such as these are offer waves. They’re the signal that precedes an incipient transaction. If they are important enough to the individual, and if they’re important to enough individuals, they represent value potential. For example, unease about the time commitment and cost of acquiring a traditional 4 year degree could be an offer wave that, when absorbed and confirmed, becomes educational innovation, the formation of online for-profit degree courses, and ultimately Coursera and Masterclass. Concern about the palatability of dogfood could become The Farmer’s Dog, or A Pup Above or one of many more entrepreneurial initiatives. Feeling lonely sparks the $3 billion online dating industry, or Meetup.

None of these businesses are real in their pre-existence as consumer unease. They are potential. Every firm, every business unit, every industry, every innovation begins as a quantum object we call consumer dissatisfaction. Every firm needs to begin with a stash of value potential. Every firm needs to be able to exercise empathy to detect the signals, understand the feelings of the emitters, the dissatisfied consumers, and translate them into commercial possibilities. These firms need the creative imagination and the resourcefulness to devise and run multiple probes into these possibilities, a portfolio of experiments in activating potential. Some will work in generating a confirmation signal that the consumer determines is the mirror image to their unease. Many experiments won’t work. The process is probabilistic. It might be possible to improve the probabilities in your firm’s favor by running more experiments or becoming better at absorbing offer waves. Or it might not.

Whatever the case, identifying and accumulating value potential is a necessary capability of every successful firm. Without it, there is no success. It requires deep, intimate understanding of the consumers, and a commitment to interpreting their offer waves. It requires the humility to know that it’s hard to perfect the process, and that there will be a lot of misinterpretations and errors.