Re-thinking The Role Of The Consumer In The Business System: Making Six Strong Connections.

A breakthrough paper published by Dr. Per Bylund and Dr. Mark Packard in January 2021, titled Subjective Value In Entrepreneurship, points to ten radical shifts in business thinking. We consider each one in turn. This article is number three in our series. (Previous articles here and here.)

Producers produce, consumers consume. Producers innovate, consumers enjoy the benefits of innovation. Producers pursue new ideas and new economic value, consumers evaluate and choose.

These are typical mental models of the business system. What if they are painting the wrong picture? What if, in representing the flow of production, innovation, ideas and value from the producer to the consumer (or the B2B customer), they are missing the fundamental mechanism of economics?

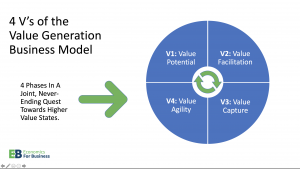

That is one of the questions asked by Dr. Per Bylund and Dr. Mark Packard in their paper Subjective Value In Entrepreneurship. In it, they propose a different image. Rather than a one-way flow of value from producer to consumer, they suggest that the producer and the consumer are equally engaged in a joint quest for value. The flow is two-way, not one-way.

One of the implications of this new perspective is to attach greater importance to the connection between the entrepreneur and the consumer, and to study this connection with greater intensity, rather than to focus on the behavior of the entrepreneur or the behavior of the consumer in isolation.

To immerse ourselves in this new way of thinking about the consumer’s role, a new mental model helps. In the new model, the consumer can be viewed as a dynamic bundle of connections to various resources. The consumer is assembing a system – to run a household, or to run an office, or to implement some specific task in as efficient and effective way as possible, i.e. best result at lowest cost. To supply the system with the required resources for its operation, the consumer connects to supply sources: for the household system the connections might be to a supermarket, a dry cleaner, an array of other retailers, a few gas stations, the local water and energy suppliers, audio and video entertainment services, internet and PC, some expert services (an electrician and a plumber, for example), one or more schools, doctors and healthcare services. There are many more of course. Think of a cloud of service connections surrounding each individual consumer and family. We can imagine a similar cloud for a B2B customer.

Whether consumer or customer, the value generation system is big and complex.

A producer who seeks to provide services to the consumer should first develop the mental model of all the existing connections the consumer has already assembled in their cloud, and is currently monitoring, managing and evaluating. For each one, the consumer continuously applies a set of value questions: was my most recent experience as valuable as I wanted it to be; do I continue to rank the value of that experience value higher than alternative satisfactions; do I feel the cost of exchange is less than the value experienced? This ongoing valuation is a dynamic swirl of continuous change, with different satisfactions and services simultaneously rising and falling in their relative ranking in the consumer’s mind.

With each act of valuation, the consumer emits a signal for the alert entrepreneur to pick up: dissatisfaction or satisfaction. The signal can be understood in terms of the consumer’s interaction with the world of goods and services providers, in the context of a never-ending quest for a higher value state. The entrepreneurs and businesses that have developed the strongest connections to the consumer will be best placed to intercept and translate the value-seeking signals.

The Six Strong Connections.

Alert businesses develop their connections along multiple dimensions;

The Information Connection: consumers are imparting information in their desire for greater value, and the smart business develops excellent information-receiving capabilities. The well-tuned connection is not so much information-gathering (i.e. intentional queries such as surveys) as a cultural disposition to hear and listen, especially at the front lines of direct contact with customers.

The information connection is two-way. Successful businesses fine tune their information provision to the customer, aiming to ensure that it is personalized, specifically relevant to a declared value desire, and additive to the knowledge they need to support their decision-making. Happily, “spray and pray” advertising tactics have been abandoned. Personalization of digital communications is a big advance for businesses, so long as they avoid the feelings of “interruption and annoyance” that can be the unintended consequence.

The Value Proposition Connection: from the listening connection, businesses can craft a customized value proposition, a proposal to address the customer’s search for greater value. This connection must also be two-way. How does the customer react? What is the level of belief? Is the customer prompted to learn more about the firm making the proposition? How does the customer feel about this value proposition compared to alternatives? If there is no feedback loop, the business is unable to answer these questions and unable to advance further through the value process.

The Evaluation Connection: consumers are engaged in continuous evaluation of their alternatives within the value system they have created for themselves. Businesses aim to be part of the evaluation process, providing knowledge where it is requested, and responses where they are called for.

The Exchange Connection: too often, it is the exchange connection between customer and provider that is emphasized at the expense of all others: it becomes the sole end of interaction for the business, whereas it is better (and more profitably) seen as one component in the cloud of connections surrounding the consumer. Certainly, a completed exchange connection – i.e. an economic transaction – indicates a successful response by a business to a consumer’s signal; however, it does not say anything about the probability of future connections.

The Experience Connection: subjective value is experienced uniquely by the consumer, so this connection is the most distant for the producer. The only role is as observer, monitoring the experience. The monitoring can be funneled through feedback loops to the designers tasked with making the experience as valuable as possible.

The Assessment Connection: the consumer’s assessment of the experience is more accessible to the producer, because the consumer is much more liable to articulate the details of the assessment, whether as complaints or praise. A strong connection would deliver far more nuance, of course, especially in the consumer’s conditional language of “It would be better if….” or “I wish…..”.

When business truly grants the consumer / end-user the role of equal partner in co-navigating towards a higher value, these six two-way connections are established, always open, and serve as freeways of co-creation.