25. Peter Klein on Organizational Designs

Austrian economics has valuable and important things to say about organizing entrepreneurial firms.

Organization can make a crucial difference to entrepreneurial success. Ideas alone are not enough – execution is needed and the details of execution are important. The entrepreneur must design an organization for detailed, effective and efficient execution. Some entrepreneurs shy away, thinking it drudgery. That’s a mistake.

Key Takeaways and Actionable Insights

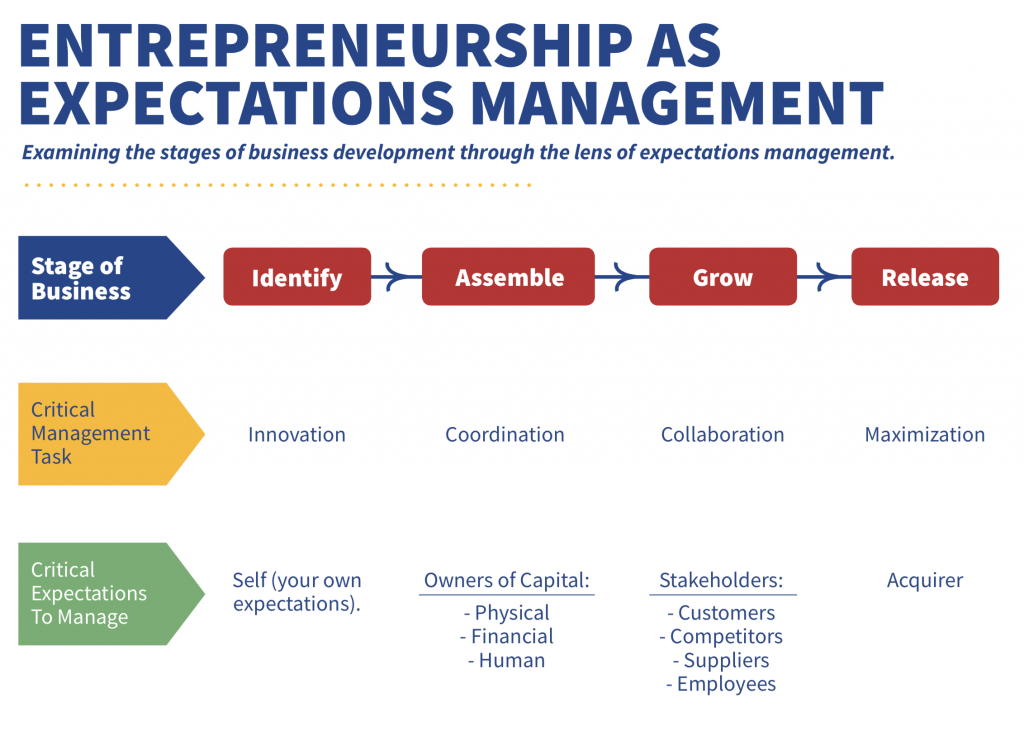

Organization is never static, but always dynamic. It’s not a structure, it’s a process. It’s your business model. It’s the collaboration that achieves the desired return on the entrepreneur’s imagination.

Austrian economics doesn’t prescribe a fixed way to “do” organization (unlike the rules- and framework-based approaches of consultants and organization gurus). It provides the right way to think about organization.

Organizational design starts with the entrepreneur’s ends in mind.

The purpose of the organization is to create customer value. Everything about the entrepreneurial firm is customer value, and so organization must be all about customer value. Elevate those elements that deliver customer value, and eliminate those that don’t. Everything that is not customer value, or gets in the way of creating customer value, or diverts resources from customer value, is waste and inefficiency.

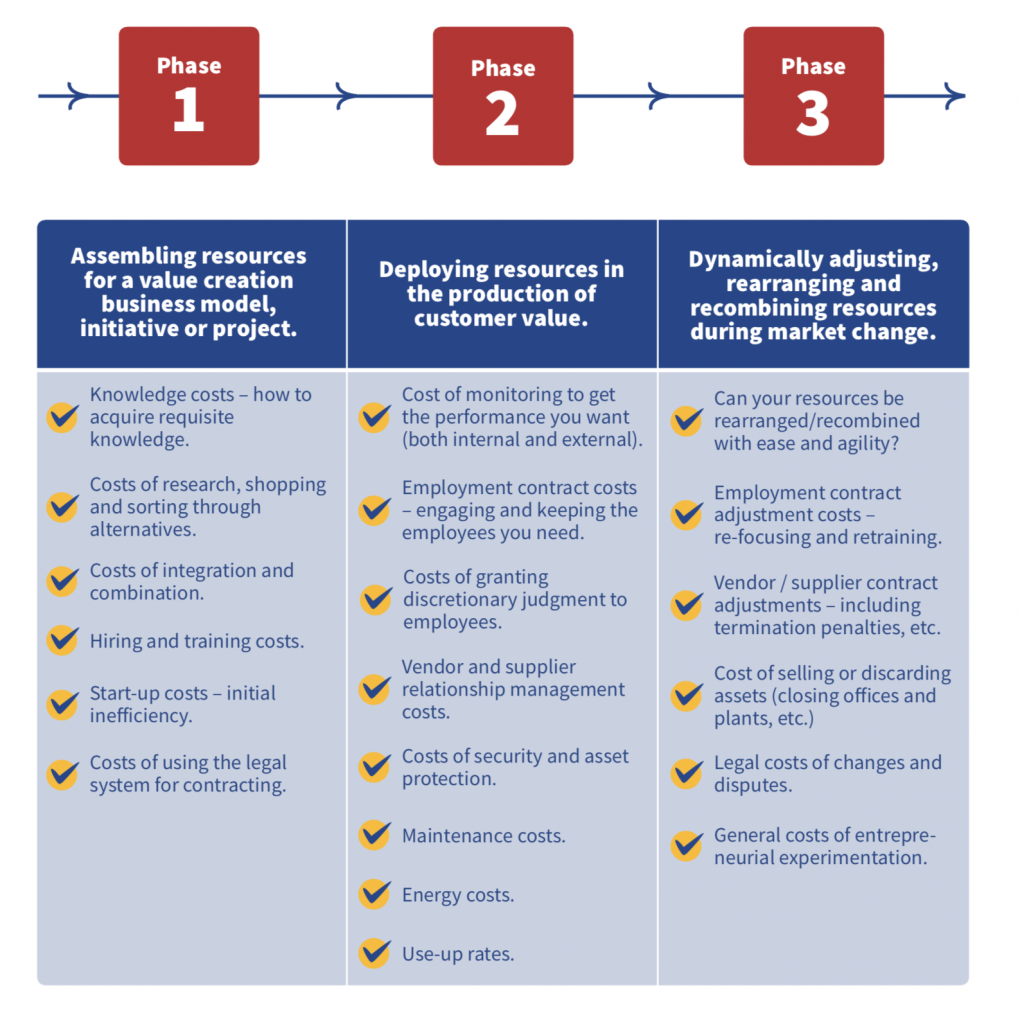

Start with the best combination you can – in the current moment – of people and resources and capabilities to create the most customer value possible.

Delegate as much entrepreneurial judgement as you can – to people with the same customer value-creation focus as you, but greater expertise and knowledge in specific areas of the business.

Hire good people (or engage good contractors and vendors) who have the right skills and experience for a specific task or field, and then give them as much authority as possible. Don’t worry about over-delegating. Rather, worry about retaining too much control and becoming a limiting factor. Employees may find better ways to utilize an asset or expand a capability than you could have done in their place. They may show more ingenuity. Make sure your organization is consistent with the most productive use of available resources. It’s becoming more and more inefficient over time to exercise authority through control mechanisms. You can’t afford the transaction costs. By delegating, you lower your monitoring and management costs.

The owner-entrepreneur’s role is to design the rules of the game: making specifying decisions and determining how performance will be evaluated.

You retain ownership control by making what Peter Klein calls specifying decisions up-front: how you are going to run the business, tight or loose; defining in advance what discretion employees have, so that they don’t have to ask about every decision.

The second tool of control is defining the measurements of success and holding your team members to your metrics.

Outsource as much as possible.

The entrepreneur defines what resources and functions are crucial and proprietary to the business of customer value creation, and keeps control over them. Everything else can be outsourced – items like payroll services, accounting, transportation, legal, anything that constitutes overhead, and any tasks that are routinized. Just make sure there is no possible damage to the customer experience.

Employment contracts and compensation systems are tools of entrepreneurial control.

The specifying decisions can often be captured in the employment contract, where decision rights can be traded for benefits, and incentives can be defined to motivate the right levels of performance and the right feelings of participation and motivation. Go-getters and exceptionally creative people can be turned into “proxy-entrepreneurs”, exercising entrepreneurial judgement that is derived from the owner’s original judgment. There are no hard and fast rules about this trade-off, and it’s often a matter of gut feel. The savvy entrepreneur constructs a mental model of how the organization operates when it’s “just right” and makes adjustments when it’s not.

How you finance your business has major implications for your governance of your own company.

Venture capitalists want a major say, often a board seat and supervision of critical decisions. Lenders may have covenants that affect your governance decisions, and most definitely affect reporting. Friends and family will want to look over your shoulder, at minimum. When you are planning your financing, be sure to think about how it will affect your organization, and whether you want to accept the inevitable constraints.

In all cases, be ready to make adjustments to your organization design, your specifying decisions, your resources, and your metrics.

The entire point of flexible, dynamic organization is to facilitate change and adjustment on the fly. Plan to monitor continuously, and make changes whenever indicated. Never get locked in to a poorly functioning organization: change it.

DOWNLOAD

Download the Organizational Designs PDF (103 KB)