19. Per Bylund: ACT! How To Apply Austrian Capital Theory In Modern Organizational Design, Contemporary Business Structure, and A High Response Business Model

Austrian Capital Theory (ACT) sounds arcane, academic and complicated. In fact, it’s the key to modern organizational design, cutting edge business structures, and the high-response business models leading entrepreneurs deploy to win in today’s business environment.

Show Notes

Austrian economics recognizes that capital and resources are so varied and different today that agile entrepreneurs can combine them and recombine them in ways that are highly differentiated – even unique. Every firm is a capital structure that is in continuous flux, as the entrepreneur changes and adjusts to create new value in response to marketplace and environmental changes. Therefore, the whole economy is a changing, rapidly evolving capital structure, generating economic growth. It is the appreciation of the need to continually shuffle the firm’s capital combinations, and the mastery and agility in doing so, that marks the Austrian Entrepreneur. He or she is an orchestrator of capital, buying and selling capital goods and combining them with new and retrained workers to change production processes, scale up to new levels of efficiency, and to solve customers’ problems in new ways.

The purpose of the orchestration function is to achieve the highest return on capital by creating the most customer value. The value of capital is the future revenue streams it generates from customers, and revenues are a reflection of value created. Entrepreneurs examine every piece of capital, and every capital combination, to measure how much value creation it contributes. Could it do more? Can the entrepreneur render the capital more productive in maximizing value at the end of the production chain?

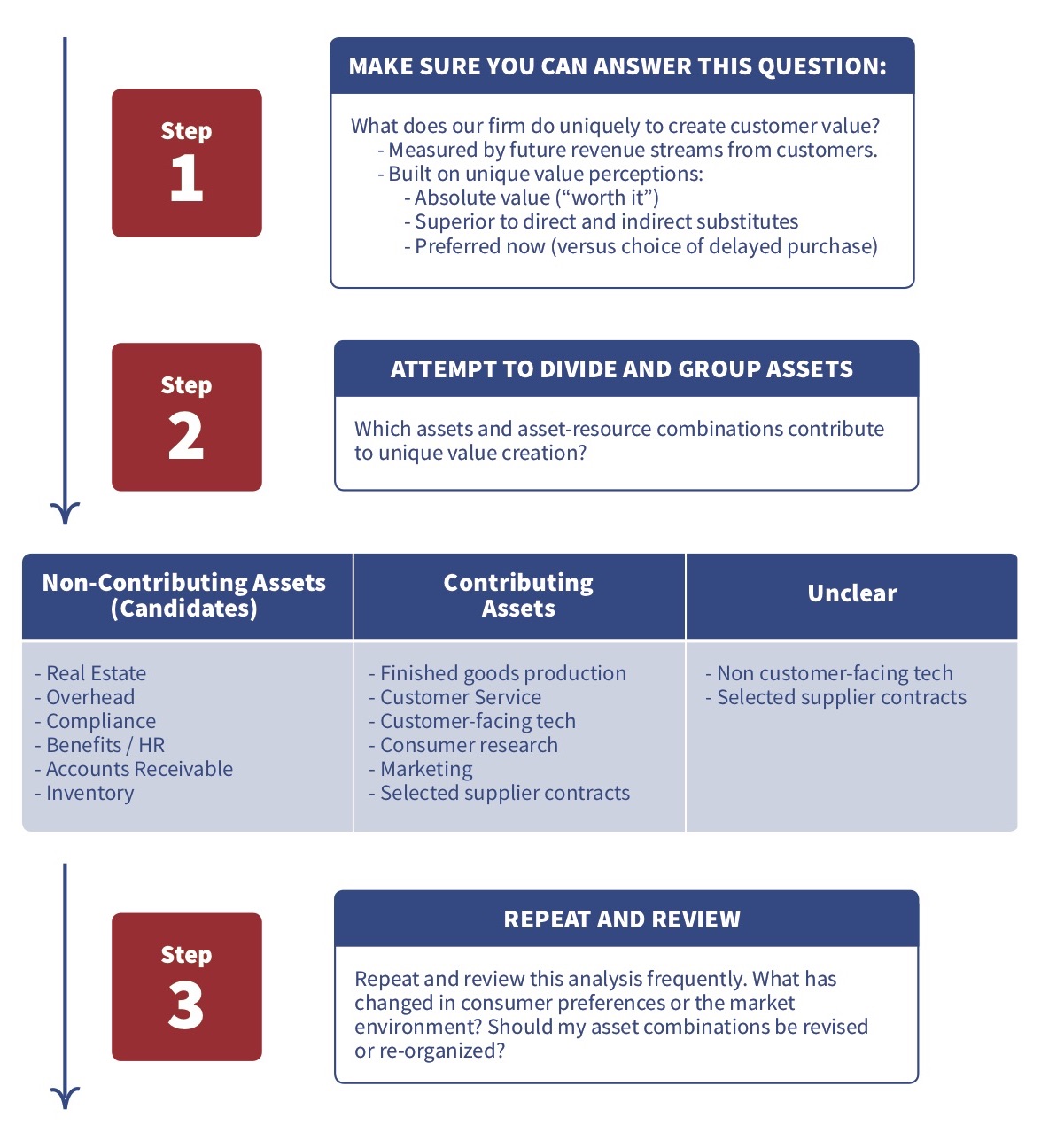

How can entrepreneurs assess whether their combination of capital assets is right? The managerial accounting of Austrian entrepreneurs is not identical to formal financial accounting. A conventional balance sheet is not going to tell the truth about the money-value of assets, since it is not based on assessing future revenue streams. And this year’s P&L is of little use since it is static and backward-looking. How can entrepreneurs differentiate between assets that it merely feels good to own and assets that genuinely create consumer value and future revenue streams? It’s not easy, but there are two useful steps, both of which focus you single-mindedly on the consumer.

- Root out those assets that clearly do not contribute directly to consumer value, or clearly contribute very little. An office building might be one such example. It’s nice to have a central office, but couldn’t your employees contribute as much from a remote location, so that you can eliminate the cost of centralization?

- Examine capital combinations that could contribute more if they are rearranged. A server + software + trained personnel is a productive combination. What if the entrepreneur could ditch the server and rent computing power from AWS? What if the savings could be reinvested in more training for the person or better software? Would this rearrangement contribute more to consumer value? Renting rather than owning assets is one way to add dynamic flexibility to the firm.

The entrepreneur should focus the firm on what it alone can uniquely do for its consumers and customers. Outsource everything else. The firm is a necessary vehicle for the entrepreneur to take ideas to market to earn a profit. It is at its most efficient when it is 100% focused on what it does uniquely: its unique brand, its unique processes, its unique recipe, its unique design, its unique functional and emotional benefits for the consumer. Everything else should be stripped away. The necessary infrastructure can be rented or outsourced. If you own 10 computers and have 10 people sitting at them every day, it’s hard to identify what productivity you are getting out of each of them every day. If you don’t own them, and you are thinking rigorously about the future streams of consumer value your firm is producing, you won’t feel locked in to your current capital structure.

A “capital-lite” structure in no way reduces the market value of the firm – in fact, it can increase it. In the past, companies were valued based on the assets they owned, as captured on the balance sheet. But this valuation method was based on an assumption that the assets were owned because they produced consumer value and contributed to profits. What if the assets are not contributing to future profit? They become a liability. Firms like GE are finding this out today – they own a lot of non-contributing assets and face major transaction costs in shedding them.

There is no need to own consumer value-producing assets. You need to control then and have the rights to utilize them to produce value, but not to own them. In venture capital markets, it is common to see firms change hands at a price that represents a high multiple of revenues or of earnings, even if the traditional capital base is insignificant. Assets that don’t appear on the balance sheet, like brand and a loyal customer base, are more important than those that do.

ACTIONABLE INSIGHT: The Austrian Entrepreneur reviews combinations of capital and labor and non-capital resources at every moment, seeking ways to improve that combination for the consumer’s benefit.

The single-minded focus is on consumers and their changing preferences and the consequent implications for responsive change in the capital structure of production.

DOWNLOAD

Download Austrian Capital Theory at Work PDF (97 KB)